Unaccompanied minors and the phenomenon of migration

Asante Wiafe | 11 Mar 2018

Recent scholarship has highlighted the peculiarity of unaccompanied minors (UAM) seeking refuge in developed countries. Considering their numerical strength in proportion to the general migration flows across the globe and the peculiarity of their situation, unaccompanied migrants have become an important category of present-day phenomenon of migration. Circumstances under which they take their flight and migrate vary, but as a sub-category of migrants who leave their home countries without the care of their parents, adults or legal guardians, their situation calls for more attention.

Migration – be it immigration or emigration – has been part of human society from time immemorial. Throughout recorded history, people, for various reasons, have moved or have had to move from one place to another. The phenomenon of migration is complex, especially when one considers the underpinnings that shape people’s thoughts and inform their decisions – individual or collective – to move. Factors that inform people’s decision to cross borders to other lands are many, but can be broadly categorised into economic, political, environmental and socio-cultural conditions where their movements have been driven by war, oppression and want.

These factors may be considered push or pull. In the former sense, unfavourable conditions such as protracted armed conflicts, persecution, abject poverty, political instability and insecurity push people out of their homeland to seek solace in a destination country. In the latter sense, political stability in advanced economies, coupled with high level of development and better living conditions serve as pulling factors attracting thousands of people into those economies. Over the years, the latter factors characteristic of European countries have been exerting a high level of pull effect on immigrants, including UAMs, trying to reach Europe.

Between January 1993 and May 2017, United for Intercultural Action’s Death by Policy document recorded a total of 33,305 documented deaths of refugees and migrants attributable to border militarisation, asylum laws, detention policies, deportations and carrier sanctions in the European Union. Among these deaths have been children of all ages who got drowned, suffocated in cargo containers, frozen to death in refrigerated lorries, shot by police or blown apart by land mines.

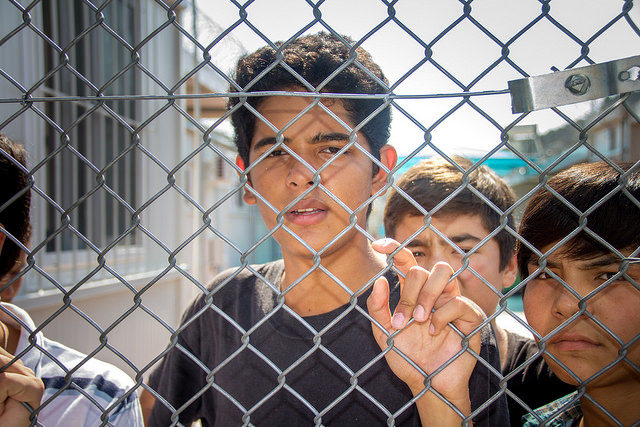

The year 2015 was the deadliest on record for migrants and refugees attempting to get into Europe. More than 3,700 people – the majority on sea crossings between Libya and Italy or Turkey and Greece – died. Up until 2015, scores of people had been taking the perilous journey of illegally entering the shores of Europe. When scores of drowned bodies were washed ashore on the Canary Islands, then the international media took notice, consequent upon which the authorities took action to help stem the tide of illegal migration flow into Europe. There is an increasing rise in the number of people attempting to reach Europe, regardless, thanks to the huge wave of refugees fleeing from the wars in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and some parts of sub-Saharan Africa, coupled with the truly desperate economic migrants who consider the grass to be greener in Europe. Among these categories of migrants are children who – whether they left on their own or got separated on their way – are neither being cared for by their parents nor caregivers. Officially categorised as unaccompanied minors (UAM), they are exposed to high level of vulnerability and as such require special care.

The unaccompanied minor: Who fits into the category?

Different legal systems have different notions of who a minor is. Notwithstanding, there is a near unanimity in terms of age, as nearly all definitions of minors consider the age of under 18. The same is true in defining an unaccompanied minor. According to the UNHCR, “An unaccompanied child is a person who is under the age of eighteen, unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is, attained earlier and who is ‘separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so”.[1] In the reasoning of the UN, the scope of the term covers “minors who are without any adult care, minors who are with minor siblings but who, as a group, are unsupported by any adult responsible for them, and minors who are with informal foster families”.[2] Unaccompanied minors need special attention and deserve a special place in policy making. It is about time policy makers took their matter with all the seriousness it deserves.

[1] UN HCR Guidelines and Principles (1997), op. cit.

[2] Report of the UNHCR (1997) (A/52/273), op. cit., para. 2

Leave reply