Brexit, Northern Ireland, and embargoes: is Irish unity on the cards?

K.A. Dhananjay | 21 Jan 2021

From January 1, the United Kingdom (UK), as part of its last-minute Brexit trade deal, formally left the European Union’s (EU) single market system. This meant that the EU’s customs and trade regulations do not affect the UK anymore. While the rest of Britain exited from the EU, Northern Ireland (NI), at least economically, remained within the EU’s trade framework. The UK brought this to avoid an impending land border with the EU through Ireland which could have severely affected the movement of supplies into NI. Though a sea-border was found as an alternative, it did more damage to both trade and politics in NI. As a result, the future of NI-UK relationship was threatened with NI opting for Ireland as a reliable trade partner than ever before. But as speculated, with Britain’s diminishing influence in NI, has talks on Irish unity resurfaced in the island? Has Brexit become a “Harakiri” moment for the UK? Let’s see.

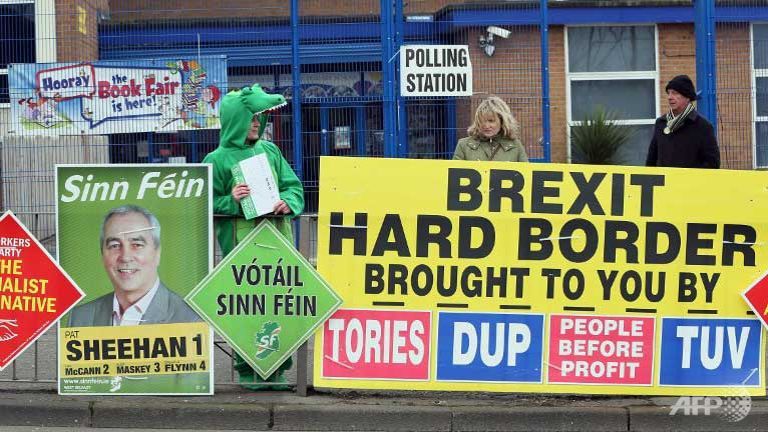

Brexit as a political phenomenon was a highly impactful one. When the UK decided to leave the EU back in 2016, there was an amount of uncertainty within the EU and beyond. The EU primarily had concerns regarding borders, immigration, and trade with the UK after it departed from the organisation. The UK itself was in a tough position to decide whether it should be a “hard” or “soft” Brexit. While Hard Brexit meant a complete break in UK-EU relations, including the UK leaving the EU’s single market system. Whereas a Soft Brexit implied a milder approach that advocated for a closer economic relationship between the UK and the EU and necessitated for the UK to remain in the EU’s single market and customs union. Moreover, the question of a hard border in Ireland was also detrimental to NI economically. Hence, given these considerations, the UK decided to keep a mixed approach; hard Brexit in Britain and soft Brexit in NI through a Sea Border.

Soft Brexit in NI implied that the land border with Ireland was almost invisible for trade. The UK, to formalise this special arrangement, had made appropriate amendments to the initial Brexit Withdrawal Agreement in 2020 and later even created a separate NI protocol that charted out the rules and obligations associated with trade and customs. With the introduction of the protocol, NI now became a part of the EU single market system and customs union, hence EU- mandated customs rules were also applicable to all goods arriving in airports and ports, including those from Britain. However, to avoid food supply shortages, a three-month or in certain cases (chilled meat like sausages and mince) a six-month “grace period” was granted, wherein food supplies could be transported from Britain to NI without filing customs declaration. Besides, the protocol also introduced the “trusted trader scheme” (TTS) for British businesses trading with NI to avail tariff-free movement of goods. Yet, there is more to this than meets the eyes!

Most of NI’s food supplies come from Britain. Albeit, during the first week of January, Northern Irish supermarkets and businesses faced a shortage of supply from British producers owing to the non-filing of paperwork related to TTS. Even Supermarket chains like Sainsbury’s have warned customers in NI stating that they may not be able to provide certain British products due to new regulations. Inter alia, a recent poll also suggested that 40 percent of British firms plan to reduce shipments to NI as they fear that the new EU regulations may require higher standards than before, even after the grace period. So, a clear solution for NI was to source goods from the South of the border or elsewhere in the EU. And, this is bound to happen. In the coming days, it is expected that trade inflow from Ireland may increase, and appropriately the chatter on Irish unity may tend to resurface.

The primary reason for talks on Irish unity to garner momentum is the existence of the aforementioned trade barriers, mainly induced by Brexit. Apart from its protestant bonding with the UK, these recent embargoes have taken away one of the key links that lie between NI and Britain; trade. Hence, as the gap widens, NI, being a territorial entity as well as a in the UK, is alienated further, and its survival per se is in tatters. This definitely might worsen the status quo. Nevertheless, the UK hopes that if issues continue and go south it may invoke Article 16 of the Protocol that provides for the UK or the EU to unilaterally take safeguard measures on account of “serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties that are liable to persist.” It may seem promising, but in the light of certain procedural intricacies, that cause, again, beats the dust.

From a political standpoint, there is a mixed view of the setback NI is currently facing. On the one hand, the Unionists (Pro-UK) in NI do have concerns that the Brexit fallout has a serious impact on the future of the Northern Irish entity and fear of an unemphatic divorce from the Crown. On the other hand, the Irish Republicans (Pro-Ireland) have found merry in the recent developments. They have managed to engineer Brexit as a political rhetoric to unite and create a single Irish identity. Around this political juxtaposition, some politicians have also voiced concerns that tenets of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, a landmark agreement between NI, Ireland, and the UK which ended the decade long Irish resistance, might be threatened since the agreement affirms that NI remains an integral part of the UK, unless decided through a referendum otherwise.

In tandem with former First Minister Lord Empey, it could be easily said that the Irish Sea border was indeed “the most significant change” that took place since the partition of Ireland back in 1921. Though Brexit was a pan-UK problem, the case of NI suggests that Downing Street was in a hurry to meet the deadline. By the time the deal was finalised, the UK never knew what it would face as repercussions in NI. Although the UK has denied any mishap in trade between Britain and NI, the apparent “teething problems” to which it agrees, seems to have coughed up both the economic and political equilibrium in the Irish Isles.

As time progresses, Ireland may become an alternative to the UK in NI, at least in terms of trade. But, will it become a political player in NI? That is still left to the prevailing constitutional and political mechanisms of NI and the UK, still that does not mitigate the possibility of a United Ireland, given how Brexit turned out. Importantly, NI never signed up for any of this. In fact, NI, during the Brexit Referendum, had voted in favour of the UK to stay in the EU, yet the cards turned against it. With the pandemic still not receding, an economy in shatters, and unfurling political uncertainties, the future of NI and the UK solely rests in the hands of Westminster and Stormont alone. Perhaps, this is a litmus test for the UK’s territorial integrity as a whole. If not now, there will never be a chance for the UK to regain its foothold in the Emerald Isles.

Leave reply